Auto Week

The Case of the Phantom SkidmarkAnalyzing a car crash is a complex, expensive undertaking – especially when the federal government is involved

By Charles Fox

Major failures can cost millions. Lawyers call expert witnesses. Behavioral psychologists investigate drivers; engineers examine the dynamics and design of cars and highways. The science of crash investigation got serious when UCLA founded a Traffic and Safety Institute in the mid-’50s.

Doctor of engineering, William Blythe, a leader in the field, has investigated crashes for the last 19 years. “When I began,” he says, “there were two or three others in California. Today there are 20 or 30. I don’t know that the insurance crisis has affected the business, but increasingly sophisticated legal work is being done in the courts. Yet judges still accept the credentials of ‘expert’ witnesses too lightly. A lawyer must be very careful who he engages — supposing, of course, he wishes an honest opinion in the first place,” says Dr. Blythe. “For all the sophistication of crash investigation today, I liken our times to those in Europe when barbers practiced medicine.”

The good doctor should know, yet he seems harsh on himself when you take into account the case of Sgt. Roderick Sinclair and the Secret Service. In this case, Dr. Blythe worked closely with crash investigator Paul Kayfetz, who, says Dr. Blythe, “is a lawyer, a certified genius, a perfectionist, and a man who any egocentric trial lawyer has difficulty working with, since his peculiar expertise will tend to take over most of a case.”

Paul Kayfetz makes movies recreating people’s last moments. He is considered the Steven Spielberg of crash reconstruction. Consider the case in question, one which Dr. Blythe regards with satisfaction, since “it is seldom one gets carte blanche where money is concerned.”

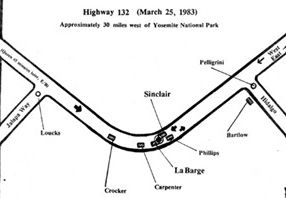

When Queen Elizabeth II visited the Yosemite Valley in March 1983, Sinclair, a deputy sheriff in central California’s County of Mariposa, was appointed to “clear the way.” He was driving his 1978 Chevrolet Impala west on State Route 132, a two-lane country road winding through open grasslands in the foothills of the Sierra Nevada mountains. Familiar with the road, Sinclair drove quickly. He may have thought no one else was using it. He was wrong.

Coming the other way, in the van of the royal party, was a convoy of three rented cars driven by Secret Service men. Stuck behind this convoy was a lady truck driver, Mona Crocker, going home. The day was overcast, the road damp.

Ranger Dwayne Bartlow had stopped his pickup truck near the junction of Jalapa and State Route 132 to watch the queen go by. He saw Sinclair’s Impala pass and disappear over a crest. When he glanced back a moment later, he saw dust and smoke rising. Alarmed, he jumped into his pickup truck and raced toward the curve. He came over the crest of the hill to see Sinclair’s Impala badly damaged and facing back. Resting against it was a brown Dodge St. Regis. A few feet from the edge of the roadway lay the demolished, twisted remains of a blue Dodge Aries. Ranger Bartlow ran to it and immediately saw the front seat occupants were beyond help. Nearby, a third man lay on the ground. Another man was desperately trying to revive him. Bartlow hurried to them, knelt, and administered CPR. Bartlow was heard to say, ” . . . the pulse, where is the pulse?” Dazed and injured, Sinclair kept asking, “Where did they come from? Why were they in my lane?”

He figured the deputy’s car was doing between 62 and 66 mph, not 74 as claimed by MAIT. The Mariposa team then wetted down the road and showed that the deputy’s car could track through the turn without any difficulty at 70 mph, well above Dr. Blythe’s estimated speed range, demonstrating that Sinclair hadn’t simply panicked and locked up his brakes as had been suggested by the MAIT report.

And now another statement appeared to support Sinclair’s contention. A Secret Service agent in the lead car said the deputy’s car had missed them by inches. This suggested that when the deputy’s car passed it the lead car also was over the center line, since the “phantom” skidmark had now established the position of the following “death car” at the moment of impact as being exactly three feet inside the center line with its left-hand side.

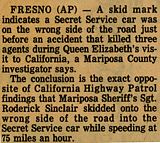

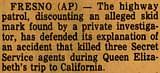

The evidence was growing. The Mariposa County district attorney, Bruce Eccerson, who had refused to file criminal charges against Sinclair, told the press there was new evidence in the case and invited MAIT to examine it. CHP Schilly’s MAIT strongly questioned the “phantom” skidmark’s authenticity, ” . . . implying, said Kayfetz, “that the mark was fabricated,” and stood by Mona Crocker’s testimony, putting the Secret Service cars in their own lane all of the time.

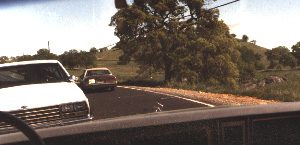

The Mariposa team, continuing its investigation, now began making movies. Using cars identical to those involved in the accident, it tried various scenarios. It placed the Secret Service cars in a range of positions relative to the center line and ran the cars at both MAIT’s speed estimate and at Dr. Blythe’s estimate.

The Mariposa team, continuing its investigation, now began making movies. Using cars identical to those involved in the accident, it tried various scenarios. It placed the Secret Service cars in a range of positions relative to the center line and ran the cars at both MAIT’s speed estimate and at Dr. Blythe’s estimate.

Cameras were set up precisely at each driver’s eye level and at each intersection where there had been witnesses. Electric timing equipment was then placed on the road to measure the speeds and positions of the vehicles throughout a series of mock collisions. A behavioral psychologist was then brought onto the scene to estimate driver reaction times for the deputy and the Secret Service man driving. These times also were factored into the team’s calculations. The results were stunning.

At the trial, conducted in Fresno, Mariposa County’s lawyer, Brunn, produced some startling witnesses. Among these were 50-year-old Dwight Matcalf, who drove a bus in Yosemite during the queen’s visit. Matcalf said he overheard a conversation the day after the accident between two men thought to be Secret Service agents. One man said to the other, “He was going too fast, but we were over the line . . . we’ve got to blame the locals.” According to The Mariposa Weekly Gazette and Miner, another witness, ambulance attendant Joan Tune, said that Secret Service agents had wanted to take Deputy Rod McKean with them to Yosemite. McKean, who testified he was looking down at his clipboard when the crash occurred, had facial injuries. Ambulance driver Tune had to insist that he be rushed to a Modesto hospital for treatment.

The feds, represented by the U.S. attorney’s office, intended to prove that the “phantom” skidmark was exactly that. Schilly, “expert” witness and leader of MAIT, argued that it was not real. Another “expert” witness said that it was real, but that it was made not by the right front tire of the “death car” but the left. This would move the car laterally four feet to the right, and, if you extended it back, the car never would have been out of its lane.

Mariposa County’s response was simple. Kayfetz’s photogrammetry had been so precise that he had calculated the width of the tire that left the “phantom” skidmark as 4.6 inches. The four tires from the “death car” had been sent to Herb Hinben, a tire expert in Grass Valley, California. Hinben examined the tires and reported that the right front showed a skid patch immediately before it went out of use. It also had a footprint of 4.6 inches. The other three tires were mismatched and all had footprints of five odd inches. So the “phantom” skid could only have been left by this one tire. The rightfront tire.

To deal with the feds’ contention that the “phantom” skidmark was only that, Kayfetz took the CHP’s own photos and processed them for maximum contrast. There it was. The CHP had made routine quality enlargements. Kayfetz also produced videotapes from a local TV station showing the “phantom” skid. Kayfetz was on the witness stand for over four days, Dr. Blythe for two. The highlight of their testimony came when they screened the movies they had so painstakingly made. These showed that from where she sat Mona Crocker couldn’t see the center line on the road where the cars rounded the curve.

Further footage showed that when reaction time was taken into account, it was clear that Sinclair was not reacting to the sight of “the death car” when he went into his skid, because the “death car” was still out of his sight around the curve. What he had reacted to was the lead Secret Service car coming around the corner over the center line. And since the “death car” driver, George P. LaBarge, couldn’t yet see the deputy’s car, what he was reacting to was the sight of his leader turning to get back in his lane. One of Kayfetz’s films shows the accident clearly from the dead man’s point of view. Kayfetz has a clip of such films. How normal everything appears to within a split second of the end. There is an alarming little device installed for the benefit of the jury: A light in one corner of the screen blinks a second and a half before impact. If the jury sees the light blink before the danger is apparent, the driver had no time to react. No chance. If, on the other hand, the danger is apparent on the screen before the light blinks, it may be that the driver could have done something. Like a thunderbolt from the blue, the Impala appeared to the wretched LaBarge. When he saw Sinclair’s Impala, the “phantom” skid was underway and life was over.

In the face of such devastating testimony, the feds called upon the leader of MAIT, Sgt. Schilly. But after Schilly had testified for only half a day, Judge Robert E. Coyle ruled that he was not competent to give expert testimony in reconstruction. Judge Coyle then ruled that every contention made by the Mariposa team was correct. He agreed that the lead Secret Service car was over the center line as well as the “death car” and that Mona Crocker may have thought she could see, but, in actuality, could not.

The Mariposa County team was hoping to get a 25 percent contribution toward the $4 million settlement from the feds. Judge Coyle found that the Secret Service was liable for 30 percent and ordered it to pay $1.2 million.

Schilly now has a desk job in San Diego. This case was apparently not a unique example of his orientation. In another accident, Schilly found in favor of a California highway patrolman who said he was “in hot pursuit” when he came over a hill doing 100 mph to find the road blocked by a flock of sheep. The patrolman went off the road into the desert some very considerable distance from the road, striking and killing the shepherd. Schilly ruled it was the shepherd’s fault for “stepping into the area of danger.” It was not made clear how the fugitive had avoided the flock.

Schilly is still not convinced the “phantom” skid was real. He says, “The only thing I’m sure of is that the deputy panicked and locked up his brakes.” Undoubtedly Schilly was a man caught in an investigation between two law enforcement agencies and, as he said, “. . . whichever way I came out, I’d be a loser.”

Kayfetz takes the point further. “CHP investigators are cops,” he says, “and once cops get an idea of guilt, they tend, naturally, to stop investigating an accident and start building a case.”

CHP commissioner James E. Smith issued a statement to AutoWeek which said, in part, “The court decision . . . (assigning) 70 percent of the crash responsibility to the sheriff’s vehicle and 30 percent to the Secret Service vehicle supports the patrol’s findings.”

Sinclair declined to be interviewed.

More than three and a half years have passed since the queen of England traveled down State Route 132. Thousands of words of testimony have been given. Yard upon yard of film has been studied. Untold thousands of dollars have been spent.

Despite all this the matter still has not been settled.

The case is currently under appeal. A judge in Fresno is considering arguments that, as a matter of procedure, Mariposa County never had the right to sue the feds in the first place. AW

James Fox, the author’s son, contributed to the researching and writing of this story.

Reprinted from Autoweek